The Upper Floor of the Alexander

They give us the entire upper floor—not for our security, not exactly, but because some payments clear faster than others and Tarmo’s account opens doors in Yerevan as smoothly as in Zurich. The hall breathes polished wood and hotel stillness; staff ghosts glide past with silver carts, and the walls swallow the city’s noise below.

Asdar is gone before anyone thinks to ask where. Only the echo of the elevator bell lingers—the way he moves, slipping in and out of lives, has always felt more like vanishing than arrival. I wonder if he’s gone to ground somewhere, the key and cards hidden inside him, or if he’s already crossing borders in a form that doesn’t need passports.

Mitra claims a suite, dropping onto the bed without bothering to shed her grimy layers, a grin stretching across her face at the wild relief of hot water and starched sheets. When she throws open the window and finds real curtains—not sacking or frost—she laughs out loud.

Karim drifts along the corridor, steps tentative, searching for balance on floors too solid, too expensive. The marble unsettles him; his gaze wanders, as if hunting the narrow lanes of Tangier for silly tourists and shade beneath tired palms.

Tarmo steers Mikael toward the far sauna suite, their passage silent. They stay there for hours—steam, heat, the slow bleed of cold from their bones—then dine in a private room, eating food that makes war and survival feel impossibly far away. Behind all the elegance, their exchange stays low, deliberate—like old friends checking a ledger for marks in red, past debts not yet squared.

Sandi, scrubbed and wrapped in hotel cotton, pads quietly into my room after dinner. She asks in a voice half-child, half-conspirator, “Can I sleep here?” There’s a flicker in her eyes, reminding me of cage doors closing and opening by invisible hands.

I nod, soft. “Of course.”

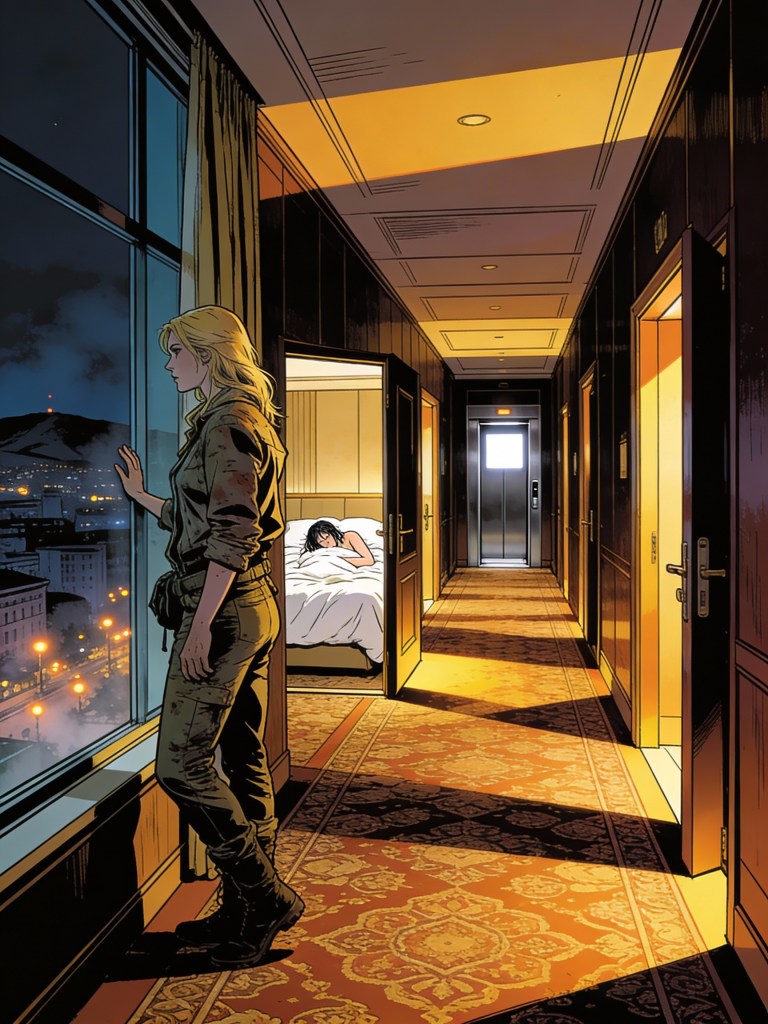

By the time I turn down my bed, Sandi is already asleep—her breathing steady, her face relaxed in the half-light.

I stand at the window, watching Yerevan’s lights shimmer through thin mist. My hand drifts to my belly again. The warmth is still there, three days constant now. My breasts ache when I move too quickly. The copper taste comes and goes.

At fifty, these should be nothing. Perimenopause, stress, altitude sickness lingering. But my body insists otherwise, humming with a certainty I can’t explain and don’t want to name.

Outside these walls, the city moves on, restless as ever. Up here, the hotel holds us—a pause, a kindness, though I know it won’t last.

Mitra

This place wraps itself around me like an anaesthetist’s mask—warmth, quiet, the soft weight of linen after a world of stone floors and winds that could skin your hands raw.

It feels as if the mountain never happened. Or maybe it just waits outside, patient, until I step back into its teeth.

I sit cross-legged on the velvet chaise in my suite, the phone warm against my ear. When the line connects, I let the lacquered calm of the hotel settle into my voice.

My sons answer together—one sounding deeper than I remember. I keep it short: “I’m well. I’m safe. And yes, eating properly.” It’s truth filtered through the lens all mothers use—steering away from bruise-coloured details, making survival sound almost routine. I let them talk about school, about the noisy neighbour’s new motorbike, about a football match played in the rain. I don’t tell them how close the snow came to swallowing me whole. That story stays mine.

When I hang up, the room stretches larger, a hush settling in. I pour a glass of water, then dial the number I know by muscle memory.

“Roger Boswell.” His voice, clipped and faintly amused, drops me straight back into the scaffolding of my other life.

“It’s Mitra,” I say. “Elena is safe.”

There’s a beat on the other end. “Safe where?”

“Yerevan. With Tarmo. Under his… provisional hospitality.”

Roger pauses, then scoffs: “Is that a neighbourhood or another planet?”

I almost laugh. “Capital of Armenia.”

“Never heard of it, sounds far off. Just tell me she’s guarded and the roof isn’t shaking.”

“She’s breathing,” I say. “That’s all I’ll guarantee. Coming down from the mountain doesn’t mean it stays behind you. Erdogan’s men will know soon enough where we landed.”

Roger doesn’t fill the silence. When his voice returns, it’s dry: “You’ll bring her back to London?”

“I’ll keep her breathing,” I say. “That’s as far as anyone can promise.”

We hang up, both aware that safety here is rented—paid for in cash and luck, and never meant to last.

Elena

I close the door softly behind me. Sandi is already curled under the heavy covers, her breath slipping into a steady rhythm. From the window, the lights of Yerevan shimmer, a necklace scattered over the hills beneath thin mist.

I pour myself a glass of water, sit on the edge of the bed, and scroll through my contacts for a number I haven’t dialed in too long. When Mrs H answers, her voice comes warm but sharp—the same as I remember—relief cleverly hidden under discipline.

“Elena.”

“I’m alive,” I say, no ceremony. “And I have Sandi. She’s safe with me. Tell Hasna—she needs to hear it from you.”

There’s a pause, just the hush of breath over the line before Mrs H responds. “You sound… tired.”

“I’ve been better,” I admit, unable to stop the slight quirk of my lips. “But I’ve been worse, too. At least we’re out of Iran.”

She doesn’t ask about the how or the cost. She never does. “I’ll call Hasna. She’s been… carrying your absence like a stone in her chest.”

Somewhere deep in my own chest, the thought of Hasna—wherever she is, maybe in some kitchen or courtyard now—hearing I made it and Sandi is safe, eases a weight I didn’t know I was still holding.

“Thank you,” I say. “And tell her… I’ll try to keep it that way.”

I hang up and sit in the honey-gold light from expensive bulbs. Exhaustion sits deep in my bones., I realise: ; my funny bone’s gone to ground with Asdar. Three days since the cave. Three days since Tarmo touched throat and sternum and the space just above my womb, creating a circuit I recognized too late.

Three days since I saw shadow-wings rise from Mikael’s shoulders in the snow.

Three days since Asdar absorbed a key inscribed with future names into his chest, where it disappeared like it had always been part of him.

The pieces are there. I just can’t make myself look at the pattern they form.

Not yet.

I.Ph.