The Black Veil.

Mrs. H rang at four-thirty, just as the October light was failing.

“Elena, darling. Don’t hang up.”

I shifted the phone against my shoulder, still wrapped in the cardigan I’d been wearing since morning. Possibly since yesterday. The heating was on but the cold wouldn’t leave—not the surface cold of autumn in London, but something deeper, bone-settled. Carpathian cold.

“I’m not hanging up.”

“You sound terrible.”

“I sound tired.”

“Yes, well.”

That particular British cadence that managed both sympathy and briskness.

“I won’t ask. But Folklore Quarterly rang this morning. They’re doing a Samhain issue, someone’s dropped out rather dramatically, and they remembered that Salem piece you did years ago. They’d like something fresh. Same territory, contemporary angle if you can manage it. Two thousand words, fee’s quite decent actually, deadline Wednesday.”

I looked at my laptop, closed on the kitchen table. I’d been avoiding it for three days.

“Friday as in—”

“Day after tomorrow, yes. I told them you’d just returned from fieldwork and were likely swamped, but they were rather insistent. Something about your ‘distinctive voice.'” She paused. “You can say no, of course.”

The kitchen was too quiet. Outside, my street carried its usual evening sounds, the 11 bus grinding past, footsteps, someone’s door closing, but inside, the silence had texture.

“What’s the angle they want?”

“Contemporary ritual practice, tattooing culture, Salem’s reinvention of itself. They mentioned some twins called the Murray brothers specifically? I’ve sent the brief to your email.”

Tattooing. Of course.

My fingers found the edge of my left sleeve, pulling it down to cover my wrist. The bruising under my nails had faded from black to a mottled purple-green. Three days since Romania and my hands still looked like I’d been buried.

“I’ll do it.”

“You’re certain? You don’t have to—”

“I’ll do it. Send me the contract.”

After Mrs. H rang off—with instructions to eat something proper and not just tea and cookies—I sat looking at the closed laptop for longer than necessary.

Then I got up, found the bottle Karim had packed in my goodie bag, and poured two fingers of Carpathian vodka into a glass.

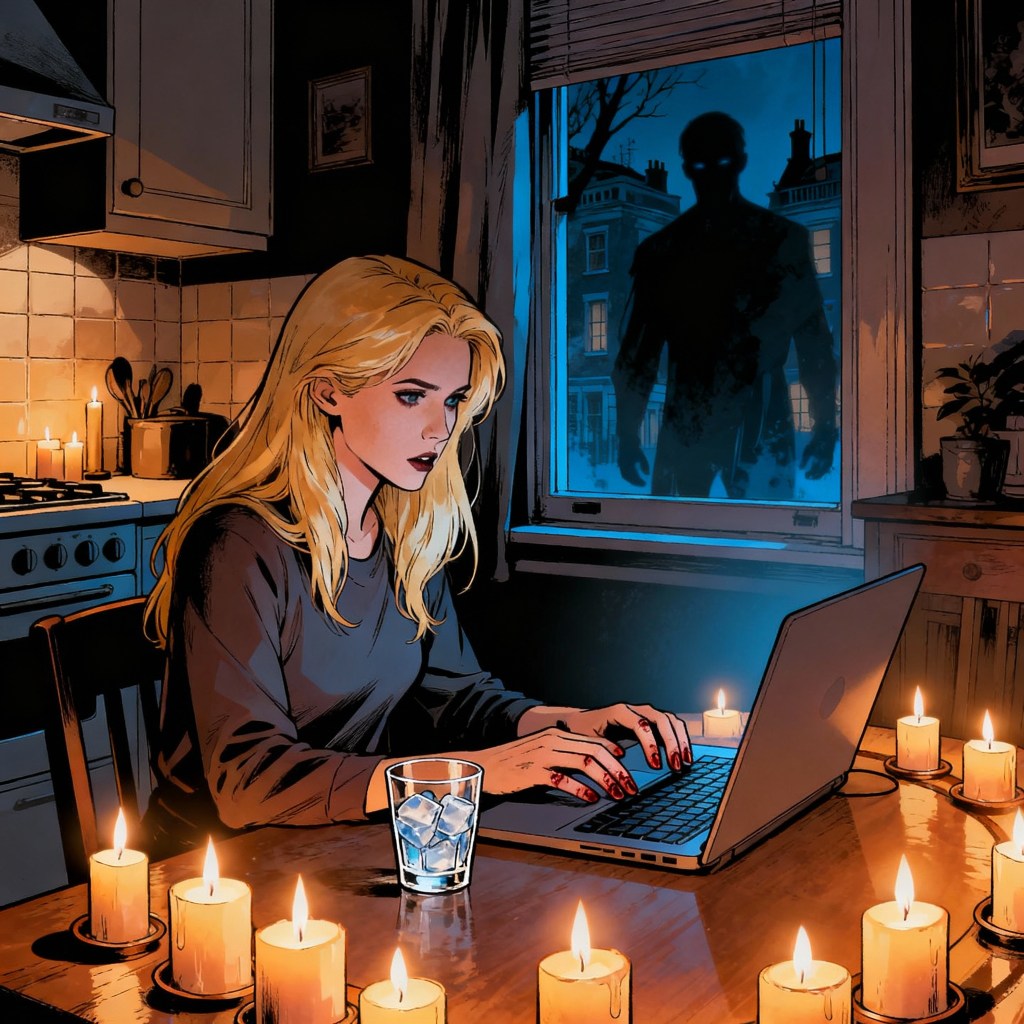

By the time I opened the laptop, I’d lit candles.

I told myself it was atmospheric. That electric light felt too harsh after two weeks in the Apuseni, after nights lit by fire and older things. That I was easing back into civilization gently.

I didn’t examine why I’d placed them in a rough circle around the table.

The brief was straightforward enough: explore how Salem’s tattoo culture intersects with Samhain tradition, focusing on artists like the Murray brothers who’ve made the city’s gothic revival their signature. Contemporary ritual, corporeal memory, the reinvention of tradition.

I knew this territory. I’d written about it before, that careful academic distance between observed practice and actual belief. How communities create meaning, how symbols gain weight through repetition, how the merely symbolic sometimes accretes into something heavier.

I opened a new document and began typing.

The connection between Salem, Samhain, and tattooing: especially as practiced and embodied by artists like the Murray brothers: offers rich ground for anthropological reflection.

My fingers moved steadily. The prose came clean, structured, exactly what Folklore Quarterly wanted. I described the Murray brothers’ work at Black Veil Tattoo: gothic black-grey artistry, Victorian mourning motifs, spectral figures. How their clients came seeking not just decoration but marking—something permanent to commemorate, to protect, to transform.

I drank the vodka. It tasted like snow and iron.

Samhain, marking the “thinning of the veil,” is traditionally a time for honouring the dead and embracing transformation.

But while I typed about contemporary symbolic practice, my mind kept sliding sideways.

Asdar’s skin under firelight. The Dacian patterns that covered his shoulders, his chest, disappearing under his collar and sleeves. Traditional ink, he’d said. Very old patterns. His family’s marks.

I’d watched him move through the forest, tracked his shadow against the trees. And once: just once, when he’d been crouched by the fire adjusting something in the flames, the tattoos had seemed to ripple. Not the play of light and shadow. Actual movement, like water flowing under his skin, like something breathing beneath the surface.

I’d blinked and it was still again.

I hadn’t asked. There were things you didn’t ask Asdar, and he’d already given me more than most outsiders ever received.

I reached for the vodka, realized the glass was empty, poured more.

The candle flames were very still.

Modern tattoos: often featuring witches, spectral figures, and arcane symbols, echo Samhain’s rituals of marking the body with meaning, creating community, and spiritually safeguarding the wearer.

My hands were shaking slightly. Exhaustion, probably. Or the vodka on an empty stomach. Mrs. H was right, I should eat something.

I kept typing.

Outside, footsteps on the pavement. Normal evening sounds. Someone walking home, someone walking a dog, someone…

The footsteps stopped.

I didn’t look up. My townhouse sits close to street level: bay window, iron railings, maybe six feet between my kitchen and the pavement. If I looked toward the window, I’d have to see whether anyone was there. Both options—seeing someone, seeing no one—felt equally wrong.

I focused on the screen.

For an anthropologist, the key is in recognizing how Salem’s tattoo culture reinvents ritual. The inked skin becomes an archive and an altar…

The cold was worse. Each sip of vodka made it worse, actually, spreading from my throat down through my chest like I was swallowing winter. But I kept drinking because Karim had sent it, because it was a tether to something real, to people who’d kept me alive in the mountains.

Because stopping felt like admitting something.

The candles reflected in the window glass. My kitchen, suspended in darkness. The empty chair across from me. The bottles on the shelf. And—

I looked back at the screen.

—a place to memorialize past persecution, to reclaim narratives lost or silenced, and to channel the mythic energy that Samhain still invokes.

Were Asdar’s tattoos protective? Or binding? Were they marks of identity, of lineage, or something more operative? I’d watched him press his palm against a tree once and sworn I’d seen the ink glow, just for a moment, just enough to make me doubt my eyes.

I’d spent two weeks documenting everything I could observe while carefully not observing too much. While maintaining that professional distance. While pretending I was studying folklore and not standing in the middle of something considerably less metaphorical.

And now I was writing about the Murray brothers’ work as symbolic contemporary practice, as invented tradition, as meaningful but ultimately decorative.

My fingers had stopped on the keys.

The candle flames were perfectly still now. Not flickering, not wavering. Still as paint.

The space felt attentive.

That was the only word for it. My kitchen: my kitchen, my home, my safe boring expensive London townhouse—felt like it was listening.

I made myself continue typing.

The Murray brothers’ art encapsulates this: their tattoos serve as visible links not to the literal practices of 1692, but to an ongoing process of memory, cultural identity, and communal healing, deeply rooted in place and time.

Was I cold because of Romania, or because something had followed me home?

No. That was paranoid, exhausted, vodka-addled thinking. I’d been in the mountains. I’d been tired and cold and working too hard. I’d seen things that had explanations, even if the explanations were complicated. Even if the explanations involved admitting that the world was considerably stranger than my dissertation committee would ever accept.

But nothing followed people. That wasn’t how it worked.

Except I could feel it. The watching. Not from the window—I still hadn’t looked at the window—but from somewhere inside the room itself. From the corners where candlelight didn’t quite reach. From the space between one breath and the next.

Tattooing in Salem is thus a new rite, where history, folklore, and the eternal pull of Samhain are not just remembered, but made permanently, unforgettably present.

I read the piece through once. My prose was clean, professional, exactly what they’d asked for. Academic enough to be credible, accessible enough for a general readership. The Murray brothers, contemporary ritual, symbolic marking.

I didn’t read it twice. If I read it twice I might see what I’d actually written underneath the words.

My cursor hovered over send.

The footsteps outside—if they’d ever been footsteps—had stopped completely. The candle flames hadn’t moved in minutes. The cold was inside me now, settled in my sternum like I’d swallowed a stone from a mountain stream.

I drank the last of the vodka. It burned cold all the way down.

I clicked send.

The laptop screen went dark.

Just for a moment, longer than the usual processing pause, longer than it should take for an email to queue: the screen was perfectly black. And in that black mirror I saw my kitchen reflected behind me: the candles in their rough circle, the empty chair, the window with its darkness pressed against the glass.

And something else.

Just for that breath of darkness.

Then the screen refreshed: Message sent.

I closed the laptop carefully. Sat for a moment with my hands flat on the table, feeling the wood grain under my palms, the most solid thing in the room.

Then I stood and blew out the candles one by one, left to right, the way you’re supposed to. I couldn’t remember who’d taught me that. Couldn’t remember why it mattered.

The cold stayed.

Outside, the city continued. Footsteps resumed. The 18 bus. Someone laughing.

Inside, I stood in my dark kitchen and didn’t turn on the lights.

I thought about Asdar’s tattoos moving under his skin. About marks that weren’t decorative. About veils that actually thinned.

About what I might have invited in by writing about thresholds while standing in one.

After a long time, I went upstairs to bed. Left the lights off. Pulled the duvet up and lay there in the cold, listening to my house settle around me.

Listening to it breathe.

I.Ph.

Author’s Note,

The Murray brothers and Black Veil Tattoo are real artists doing extraordinary work in Salem. While Elena’s supernatural unease is purely fictional, the cultural significance of their tattooing practice—and Salem’s contemporary relationship with ritual and memory—is very much grounded in fact.

My thanks to @inkedabroad for documenting this intersection of art, place, and meaning.

I.Ph.