Navigating Narva

Arriving at the University of Narva with my bag slung over my shoulder, I was greeted first not by faces but by the collision of languages: Estonian, Russian, the odd ripple of English ricocheting off the hallways’ linoleum floors. The place felt less like an academic fortress and more like a border post, every voice a passport, every silence another sort of visa.

The reunion circuit began with the Dean—a man wearing the restrained pride of someone forever balancing diplomacy and local reality. He shook my hand with just enough firmness to signal welcome, paired with an undercurrent of caution, as if every gesture here was part of an ongoing negotiation. The professors followed, orbiting with talk of research grants and half-cold coffee, their conversations weaving academic threads between Estonia, Russia, and the rest of Europe. I tried to follow these threads, but soon realised I was more of a cartographer than a participant, mentally mapping the invisible borders between people, departments, and dialects.

Government delegates eventually arrived, trailing the faint scent of protocol and paper. Their rhetoric, heavy on words like integration, progress, and fraternity, filled the room like a draft. They spoke in Estonian for gravitas, then flipped into Russian for the cluster of international students, who gathered in stubborn islands of identity: Mongolian, Polish, Latvian, tangled with the locals. I drifted among them, a stranger among familiar strangers, watching how each handshake—performative, practised—left behind a barely visible residue of hesitation.

People have never been able to guess my nationality, blond, big blue eyes, Asian features, tall, yet tiny in build, also here I could see them wonder, (I still have to encounter the person who guesses correctly; Dutch, right?).

After the formalities and an exhausting blur of small talk, I excused myself from the reception. The delegates were still circling each other in their careful dance of protocol, their conversations growing more animated as the wine loosened tongues, but never quite enough to breach the real subjects that hung in the air like smoke.

The old city beckoned through tall windows, promising cobblestones and tourist-friendly nostalgia, but I found myself drawn eastward instead. My feet carried me away from the university’s polished corridors and into the neighbourhoods where Narva’s Russian cluster clings to its own customs with stubborn tenacity.

The change was immediate. Even the air felt different as I crossed beneath a Soviet-era archway—ironic, I thought, given how history in this city loves circular logic. The careful multilingual signage of the university district gave way to something more honest, more lived-in.

Here, Russian wasn’t just a language; it was a living barricade. Children played beneath onion-domed churches, their shouts echoing Pushkin verses, as parents bartered recipes and local rumours in a cadence untouched by Estonian vowels. Small shops sold Cyrillic-labelled goods with silent pride, and the only visible sign in Estonian—”Apteek”—felt less like a welcome and more like a municipal necessity.

Vera brought me into her kitchen anyway, a faded portrait of Putin peering down from the shelf like an uninvited ancestor. “We don’t change for anyone, devushka,” she said, pouring me tea black as the river outside. “Estonia is the government. Narva is heart. You see?” She pressed a honey cake into my hand, and I understood—not in language, but in gesture—how tradition can refuse assimilation as stubbornly as winter frost.

I sat in the lingering dusk, honey on my tongue, and watched golden light gild a city at its crossroads: Estonian policy, Russian soul, and myself suspended between them. Outside, families circled in rituals both familiar and foreign, the border between realities held by little more than memory, pride, and a polite refusal to let either side win.

In that space—where languages collided and histories refused to dissolve—my role became clear. I was an outsider, yes, a memory cartographer tracing the rivers people pretended not to cross, watching old maps shimmer and disappear with each new conversation. Here, truth was never spoken outright; it settled instead like the mist, quietly, between the lines.

As the evening settled over Narva’s weathered stones, I wandered past the last ochre glow of café lights, my head still buzzing from academic rhetoric and polite refusals to talk about anything real. Karim’s zog was an understated orbit, steady but with that faint charge of expectation—a handler more than a friend, and sometimes a translator in ways words couldn’t express.

On the street, beneath crooked lamp posts and the echo of distant Pushkin, a man waited. Mikhail, the cousin, was introduced with only a sideways glance and the kind of handshake that measured, not welcomed. He wore the city’s uncertainties with ease, his speech curling in Russian, suspicious and soft.

“You’re Elena?” he asked, eyes flicking between me and Karim, as if trying to map a pattern behind my questions. “I can arrange the meeting. But things like this, in Narva, they’re not free.”

Across the river, beyond the view of onion domes and border patrols, lay his cousins—Nurgjeta and Ludmilla. Everyone assumed I was there for secrets, for some hidden report, but all I wanted was construct, and for that I needed help to make tangible the plan I had drawn—whatever the cost.

His voice dropped, nearly lost beneath the shouts of children and the murmur of a nearby market. “You’ll have to cross the river tonight. Not the bridge, of course. That’s for officials and tourists.” His gaze lingered on the black water, a shifting line between two stubborn realities. “My cousins are waiting. You cross, they talk. But when you return, you owe me a favour. No bargaining, devushka. Just trust that the river remembers its debts.”

I nodded, feeling the mist rise from the Narva, the chill that marked both the city’s edge and its soul. Karim shifted beside me, uneasy. It occurred to me that in Narva, every transaction—every interview, every shared tea and honey cake—was always a deal, even if no one named its terms.

Mikhail smiled, dry and certain. “The river keeps its own score. So do we.”

In this city, advice and integration were never simply asked or given. Understanding was paid for—sometimes in questions, in night crossings, in favours you didn’t know you could return.

So I agreed, because that’s how anthropology works in places where maps shimmer and people write their own borders. If I were after clarity, sometimes you had to walk directly into the fog.

Karim and I walked on after Mikhail disappeared into the dusk, his words trailing behind us like cigarette smoke. The river’s dark shine pulled at my thoughts. A night crossing. A debt. A favour I hadn’t yet imagined.

I needed to anchor myself before the current carried me further, so I dug my phone out of my coat pocket and found Sandi’s name. She answered on the second ring, voice crisp, like she’d been expecting me and was already halfway through a to-do list.

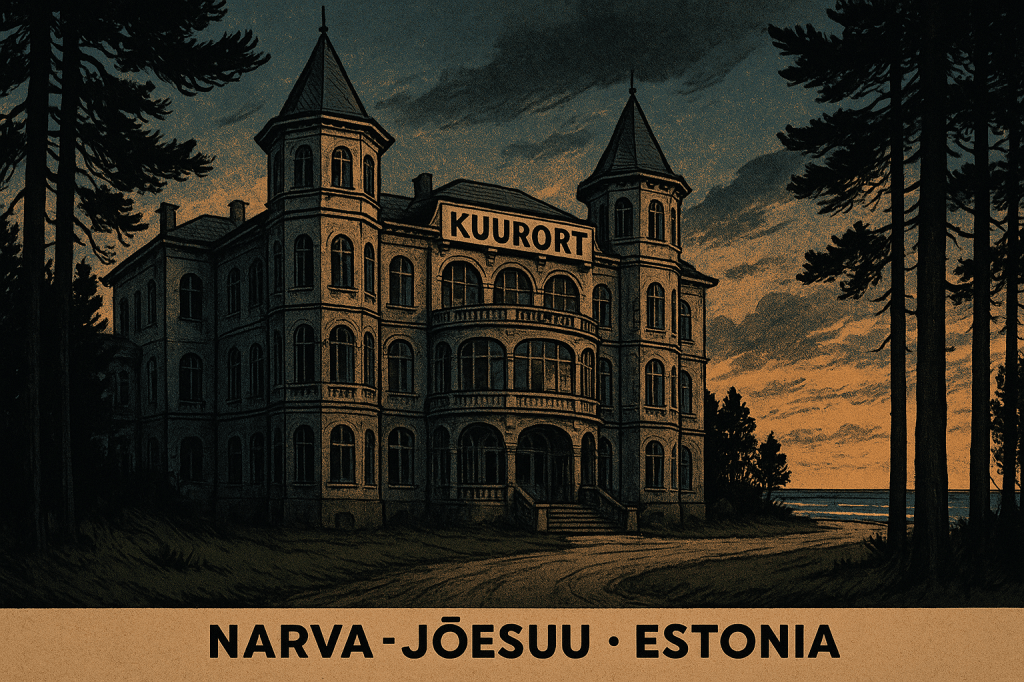

“Sandi—change of plans,” I said, keeping my tone measured. “We’ll have our meeting in Narva-Jõesuu instead. Kuuroort. I’ve reserved the upper-echelon room.”

There was a rustle of papers on her end, and then the faint lift in her voice that meant approval wrapped in curiosity. “A seaside resort for business?” she said. “Interesting choice.”

I glanced at Karim, whose expression said he’d already guessed why. “Sometimes,” I replied, “you need the sound of waves to cover a conversation.”

We ended the call quickly—no need to give the river more of our words than necessary. Plans had a way of behaving differently here. In Narva-Jõesuu, with its Baltic air and creaking elegance, the conversation might flow freer. Or not. Either way, the upper room was booked, and the next move had been set like a chess piece I’d chosen without entirely knowing the endgame.

The silence that followed felt weighted. Karim stood beside me, hands in his pockets, watching the last light fade over the water. Something had shifted between us since Mikhail’s proposition—a new gravity that made even the quiet feel deliberate.

The drive from Narva to Narva-Jõesuu is a gentle unravelling of time—a stretch of road where the city’s purposeful grit gives way to the slow, aristocratic hush of old resort towns. While Karim pilots the car, eyes flickering between the road and the mirror (always, always watching me), I catch snatches of pine forest and the shimmer of the Narva River. I can almost imagine the carriages of St. Petersburg gentry from a century past, their laughter rolling ahead to the sea.

The KUURORT restaurant stands at the very edge, a relic and a performance both. Its tower commands a view fit for negotiations or affairs, all elaborate trim and panoramic windows that catch the declining sun. As we enter, the air is thick with hints of vanilla and ocean, as if the Tsar’s cooks might reappear at any moment.

I tuck my arms to myself, trailing Karim, who unfolds into the bodyguard role with careful solemnity. His hands fold precisely, green eyes pinned to me with unwavering focus. There’s something almost comic about his intensity, if it weren’t so sincere—not a hint of distraction from his self-appointed duty. I wonder, wry and a little touched, if he got a crash course or if this fierce protectiveness just comes naturally now.

Sandi is already waiting—a precise silhouette in the gilded dusk. Her hair pulled back, businesslike, a fresh file on the table and a practised smile just a notch too wide. We take our seats; Karim settles behind me, back straight, watchful, an out-of-place sentinel among the echoes of orchestras and laughter from long-ago Baltic summers.

The meeting unfurls in polite phrases at first. Sandi outlines project failures, staff attrition, and possible local partners with the easy fluency of someone reporting from above the fray. I listen, but as she speaks, something feels… choreographed. A missing tooth in her narrative, a date that doesn’t line up with an earlier message. Her hands flutter a bit too much when referencing outside “contacts.” Her gaze flickers off mine whenever the topic skirts anything transactional. It’s then I realise: her report has the shape of truth—but none of the mess.

I pose a payroll question, feigning casual, watching her reaction. For a moment, her face tightens, just a hair, before she smooths it away with a sip of tea so composed it seems rehearsed. Yet suddenly her hand brushed mine—a touch more hesitant, more deliberate than I’d expected. It lingered there a moment too long.

All the while, Karim’s presence looms at my back. He’s so intent, so wound, I almost smile despite everything. Gentlemen once escorted ladies along this very coastline, arm in arm, for appearances and protection, while the real negotiations happened with eyes and silences. Now it’s Karim, wordless and fierce, anchoring me in this gilded theatre. His commitment feels rooted in something deeper than mere duty—a devotion that borders on longing.

Even surrounded by the grace of old Narva-Jõesuu, Sandi’s ambiguity flashed—slippery, careful, her loyalty a coin buried deep. When I finally outlined the night’s plan, she leaned closer, voice lowered to something that trembled at the edge of resolve.

Leaning back, I let the sea air do its work, and wonder at who’s guarding whom—and who in this story will slip first. I smiled, quietly sardonic, sensing the paradigm shift. The night’s plan had changed: Sandi wasn’t just my advisor—she was, for this hour at least, complicit.

“If you cross the river,” she murmured, voice slipping toward hope and vulnerability, “then I come too. I won’t just wait for you.” Her declaration, barely a whisper, cut through the bureaucratic choreography and landed somewhere raw—a kind of confession, an alignment.

Whatever debts the river demanded, we’d pay them together. Even as the world outside shimmers gold on the water, the game inside is only just beginning.

Author’s Note

Narva and Narva-Jõesuu, Estonia

This chapter unfolds in one of Europe’s most compelling border cities, where the Narva River serves as both a geographical boundary and a cultural divide between Estonia and Russia. Narva’s population is approximately 95% Russian-speaking, creating a unique linguistic and cultural enclave within Estonia that has persisted since Soviet times.

The University of Narva, established in 1999 as a college of the University of Tartu, represents Estonia’s ongoing efforts at integration and education in this predominantly Russian-speaking region. The academic and government rhetoric around “integration, progress, and fraternity” reflects real policy language used in Estonian discourse about its Russian minority.

Narva-Jõesuu, historically known as Hungerburg during the German period, was once a fashionable seaside resort for St. Petersburg’s elite. The KUURORT restaurant is fictional but draws inspiration from the area’s imperial Russian spa heritage, when Baltic seaside resorts served as summer retreats for the Russian aristocracy.

The “night crossing” referenced in the narrative alludes to the complex reality of the Estonian-Russian border, where families separated by political boundaries have historically found unofficial ways to maintain contact. While the specific crossing described here is fictional, it reflects the human stories that persist along borders where politics and personal relationships intersect.

Special gratitude to Kadri, whose scholarly rigour and firsthand experience of Narva’s challenges provided invaluable insight into the complexities explored in these pages.

May your questions outlast your certainties.

I.Ph.