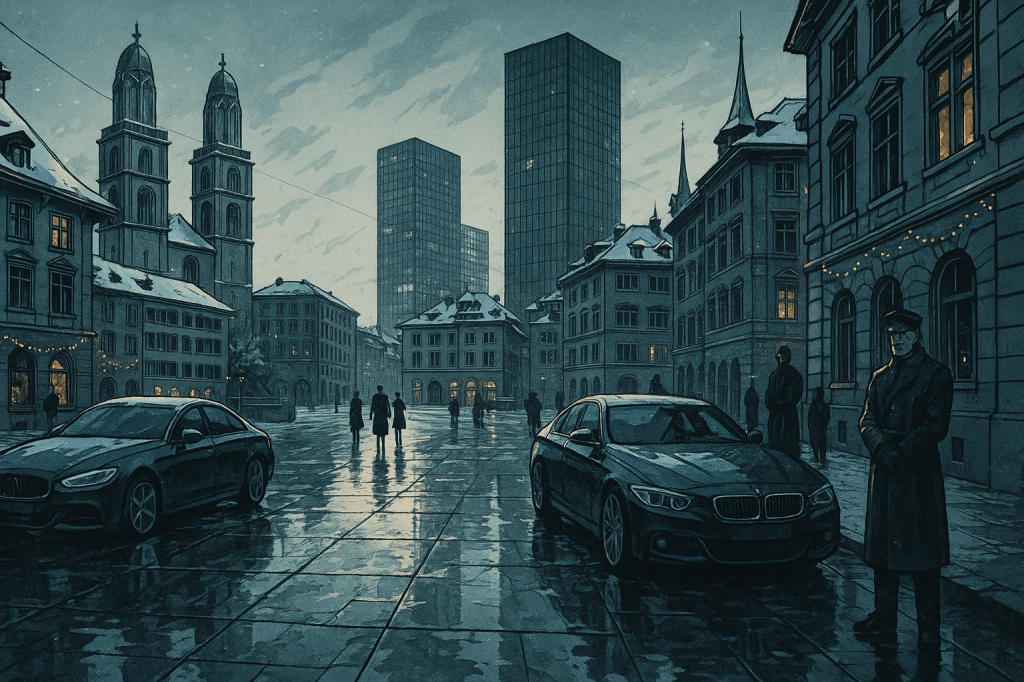

Zürich, Late Night, Kreis 7

Zürich, late. Sodium vapour stains the facades of Kreis 7, washing the curbs and empty intersections in a spectral orange that feels both alien and familiar. Outside my window, the Limmat runs ink-black beneath the bridges, swallowing up every stray flicker of light.

In my study, the paper maps of Narva sprawl across the desk like diagrams from old surgery—creased lines of possibility drawn and redrawn, growing more uncertain with every update. Each annotation reads more like the aftermath of wounds than geography. I stand at the glass, phone in hand, reading the encrypted messages bursting through in waves: Sandi’s bland words, too neutral by half; Karim’s acute, almost pleading notes; Hasna’s warnings spiked beneath careful politeness. The air inside hums with surveillance and secrets—the presence of watching eyes has seeped into the wallpaper.

Behind me, Tarmo scrolls through crisis bulletins, his voice the familiar rhythm of tired conviction. “They’ve gotten bolder in Narva. Someone’s been feeding Sandi double lines—she’s either flipped, or she’s finally admitting which side she was always on.” He pauses, letting the weight settle. “Karim’s frustrated. His leash is fraying. The situation on the ground is not what it was.”

I nod, eyes drawn to Zurich’s hush—fractured only by a lone siren threading through the night. Every update from Narva tastes like unfinished business—a city where history cracks beneath the surface, where alliances have always run in deep water.

“But it has to be you,” Tarmo says, his words carrying the weight of the inevitable. This is not an order, but an admission: he cannot run every front, not now. “My presence would be a provocation. Besides—” I feel his gaze on me, affection and calculation intermingling in a rare moment of truth. “You know those people better than I ever will. They trust your name. They still want a future, not just a payoff.”

I feel it rising—the old courage, battered now into grit. “And if Sandi’s working both sides?” I ask, voice low, almost gentle. “If she’s made me her mission?”

Tarmo steps closer, tension thrumming through him. “Then you’ll deal with her as she deserves. I can’t second-guess you from here—not anymore.” His hand settles on my shoulder. For the first time, the gesture is not possession, but a final weighing of risk and respect.

At the table, my annotated columns and analyses have become briefings for others in the field—tools that were once an academic exercise, now a blade instead of a lens. My fieldwork is no longer theoretical. I remember Narva’s fractures: Russian old men on park benches, Estonian Roma girls traded for passports, the pop-up shelters where history and crime blur into something that shaped and broke me. The anthropologist’s eye I relied on has turned into something sharper—every judgment now carries the currency of betrayal.

It feels, finally, like fate—I was always meant to return, but now as someone transformed by loss and ambition, wise to the weight of consequence.

Tarmo’s voice turns quiet, forced into the conditional. “Come back whole, Elena. I have enough battles elsewhere. The line holds here without you. But that one—they need you, not anyone else.”

I almost smile, past the ache. “We’ll see if anyone is still themselves by the time this is done.”

Above us, Zurich leans into another sleepless watch, indifferent yet comforting. But somewhere east, Narva is already tugging me back—into the current, into consequence, into the work and heartbreak of a return that was always waiting. Narva already has my name.

Zurich, Departure Morning—Elena

After nights in the embers and arms of someone who, against all odds, became my shelter and my storm, sleep comes jagged and brief.

I lie there, half-propped on Swiss linen, half-driffting, remembering how tears sometimes come to lovers afterwards—not from grief, but from the shock of being, finally, unlocked.

The tears I feel after the semen.

I feel his tears falling on my face after I felt his semen in me.

“Gods below, the man also leaks from his eyes?

Is this what happens when you cross the Alps—turn a Viking into a fountain?”

I half expect him to start reciting Rilke and darning socks.

But no—he just blinks hard, jaw set like he’s wrestling down the ghosts of his ancestors. I file away the observation as one more Zurich miracle:

Even stoic men can overflow, given the right disaster.

An old lover taught me about that: some reliefs are so fierce they leak from the eyes when no mask is left. Perhaps it’s an artist’s privilege, or simply a warning sign—vulnerability, like talent, doesn’t always come on command.

I watch Zürcher morning stutter across pale marble and fire shadows. Easy to pretend this is just another business trip: flight ticket tucked inside a worn passport, another scarf, another set of gloves. But Zurich, for all its armoured ritual, never felt mine. Not the way Tallinn or Tartu did, and Narva still might.

Airports are purgatories for the unrooted, but Swissair’s gates are almost too pristine—an oubliette for the guilty privileged. Frau R stops just shy of a formal goodbye.

Mikael presses a fresh file into my hand. “Updates from Narva. Sandi’s picture and everything we know—or think we do.” The look he gives me is clinical, then almost sorrowful. Is that how I seem to them now, boxed and catalogued?

The final boarding call crackles overhead. Time’s up. “Tarmo—”

He kisses me then, right there in the middle of Zurich airport, with Mikael watching and Frau R pretending not to notice. It’s not gentle—it’s desperate, claiming, a promise written in the language of lips and teeth and barely controlled need. When he pulls back, his forehead rests against mine for one stolen moment.

“Go,” he whispers. “Before I do something stupid like ask you to stay.”

I pick up my bag, the file tucked safely inside, and walk toward the gate without looking back. Because if I do—if I see him standing there watching me leave—I might do something equally stupid. Like, turn around.

At the gate, I finally steal a glance over my shoulder. He’s still there by the windows, a solitary figure against the grey sky, and I realise this is how I’ll remember him: guardian and threat, salvation and damnation, watching over me even as he lets me go.

The scar—the gold mark beneath my sleeve—throbs once: a signature wrought in pain, a warning that this story is far from over.

On the plane, before takeoff, I flick through Sandi’s file. The photograph shows a mouth tight, eyes almost too neutral; the résumé is aggressive in its tidiness, the sort of dossier that only the dishonest or the meticulous can maintain. My instinct prickles—no one this deep in the world is ever so . . . convenient. If she is what she says, the world is a better place than I know. I file that thought away. I’ll treat her as a variable, not an answer.

In the hush of altitude, with only the hush of turbines for company, I let myself daydream: who will be waiting when I land?

Karim, so guileless and hungry—awkward now, older from absence, perhaps angry at the wrong things. Or Sandi, the new variable, a voice become flesh at last, who has known me only as a chain of logins and cautious half-truths. I rehearse faces in my mind, annotate each with doubt.

This is the anthropologist’s curse: to enter every space as both participant and observer, empathy wrestling with suspicion, the past pressed down in my carry-on next to a fistful of Swiss francs and a phone too well-tracked to trust.

As the descent starts—clouds piling over the Baltic, ground rising to meet me—I close my eyes. I don’t know if I am running toward reckoning or simply circling back, older and less equipped for hope. If anyone asks, I’ll tell them I was in Switzerland researching legends. Sometimes, to survive, you catalogue the myth that is yourself.

And as wheels bite the Narva runway, I steel myself for the encounter: the awkwardness of Karim, the too-neat danger of Sandi, and the first hard intake of northern air—the chill that says there’s no shelter, only what I carry, only whatever I might salvage from return.

Author’s Note

Let’s be honest: if you’re wondering which bits are “fictional,” the answer is mostly the names and the order in which calamities arrived. Everything else—awkward airports, questionable coffee, legendary misunderstandings—is lived experience, lightly redacted for plausible deniability and the protection of the spectacularly guilty.

We’re shifting east now, toward Narva, with Ivangorod waiting in the wings. If you thought Zurich or Tallinn had their secrets, just wait. Border towns breed a special variety of absurdity—places where history doesn’t bother asking permission and high drama spills onto the same cobblestone as low cunning.

For the younger, or just less terminally European, who keep encountering the name Rilke: he was a poet with a direct line to existential dread—think of him as the bard of longing, solitude, and beautiful confusion. If characters start getting misty-eyed and quoting him, rest assured it’s either a genuine crisis or a spectacular case of over-education.

The biggest fiction ever invented was being right or wrong, good or bad. Everything else, including what’s in these pages, is just the local flavour of confusion.

Anyway, thanks for crossing borders (and possibly man-made ethical boundaries) with me. The stories ahead aren’t so much invented as reframed—just enough to keep your legal team and mine out of trouble. Adjust your expectations accordingly, and—most importantly—enjoy the ride.

May absurdity run in your water supply, and sanity flow in your airstream

I.Ph.