Where the River Defies Its Banks

He’s silent above me, chest rising and falling, still lost in that bruised borderland between possession and surrender. I can see traces of old awe in the set of his mouth—like he half-expects a Norse god to step through the firelight and strike him down for having the audacity to want so much, so openly.

It’s almost holy, the way he looks: wrung out, bare, as if loving me is both saving and damning him in equal measure.

For a moment, a hush stretches. Between the crackle of the fire and the aftershocks in my own body, I let myself simply be seen—no masks, no performance. I stroke his hair, damp with exertion, feel his breath stutter. The seriousness hovers on the edge of overwhelming, so I do what I always do: tip the scales.

I murmur, lips brushing his temple, “Tell me, Tarmo—did you call on Odin or Loki just now? Because I swear, I saw your ancestors lining up for vicarious thrills in the shadows.” My smile is crooked, and my voice is low and teasing.

He lets out a choked laugh, shaking his head against my shoulder, half embarrassed, half grateful for the reprieve, he mutters. “You twist every rite and runestone.”

I laugh, freer now—threading my fingers through his, letting levity break the spell. “If I’d known I’d turned a discreet Estonian magnate into a saga hero, I’d have brought my own horn of mead. Should I be worried you’ll try to drag me off to Valhalla every time the bed gets cold?”

He raises his head, eyes gentler now but still burning with that peculiar Tarmo-need—part awe, part dread, all naked. His voice is low, carrying a teasing edge through vulnerability:

“No, Elena. Valhalla would be in danger,” he whispers, mouth quirking, “or maybe you’d be the danger in Valhalla.” he whispers, “I’d rather keep you here, risking the world, every day.”

I press closer, and in the slight distance between reverence and mischief, find a place we both can rest. Intensity flickers, but so does laughter; survival, I know, means keeping both alive.

Outside, Zurich’s city lights prick through the curtains. Inside, the fire dwindles, but I feel the heat of us linger—a promise that whatever comes next will be faced together, with all the wild, defiant grace we can muster.

The next few weeks

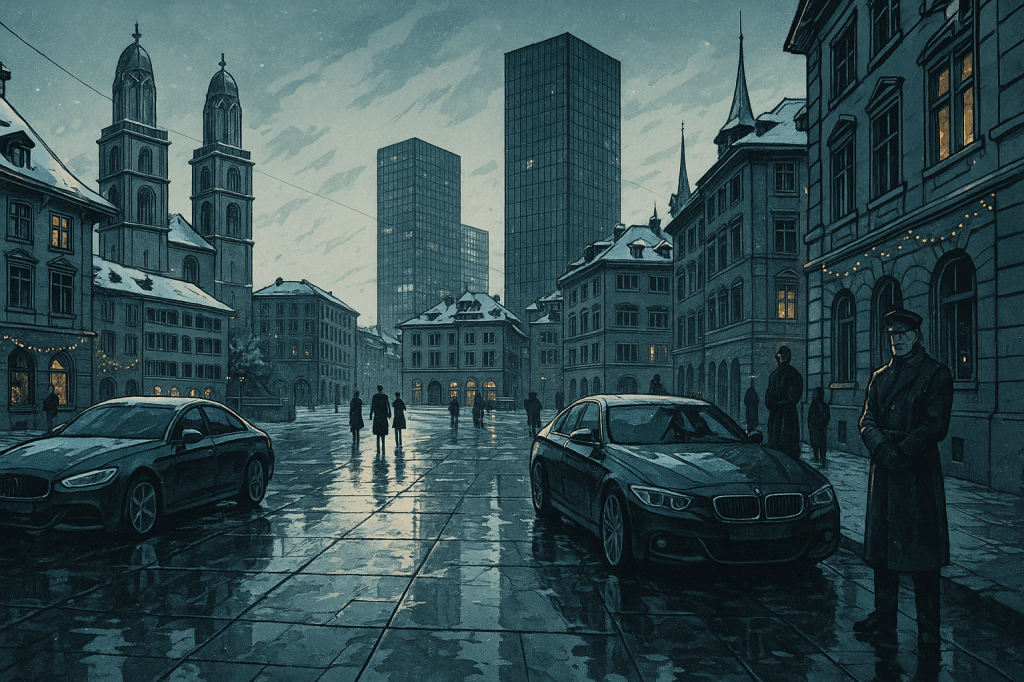

Zurich is a city built on the bones of its own legends. Every stone beneath our feet murmurs with old treaties, stubborn saints, and trickster spirits the bankers pretend not to see. In the brittle dusk, I watch the cleaning woman—her hair pinned with army precision, eyes sharp as a Protestant hymn—and imagine her as Frau Rottemaier’s lost twin, born on the wrong side of some Alpine border.

Days are now a careful choreography between calls and confrontations. Hasna on the encrypted line—every syllable laced with warning, a code within a code. Sandi, voice bouncing from Narva’s grey edges, reminds me of the wildness I’ve left behind, the kind that can’t be contained in marble halls. Marina, relentless as any goddess, still tugs distant strings; her journalist friend ends up nearly smuggled out of Europe in his search for a story, Swiss guards escorting him from the city with the polite ruthlessness of a fable’s omen. Zurich seems to specialise in this—gently, with a smile, it devours the unprepared.

Between these calls, myths slip in the cracks—tales from the cleaning woman, who swears her great-uncle once saw a frost giant striding down the Limmat on Christmas Eve, blue as glacier melt. She tells me of Frau Perchta and the Wild Hunt, of the Tatzelwurm burrowing beneath Uetliberg, of lost spirits haunting the lake if you listen near midnight. Each story lands in me like algebra, not quite solved—a reminder that not everything can be catalogued, not even my own heart.

Tarmo listens some evenings, after tactical debriefings have stolen the daylight, after exhaustion lays the guards low, and only the thick Zurich dark is left. He pretends to scoff at these stories, but I catch him, sometimes, tracing the lines of his own hands as if looking for runes. I wonder if the hunger in him—once for power, now warping toward wanting me—is kin to the appetite of those old mountain spirits. Sometimes I see it: his jaw tight, his gaze flickering between the city lights and the shadowed shape of my body in our borrowed room. He is hungry, but for what—command, or me, or some absolution neither of us can grant?

Now and then, his struggle sneaks out in the shape of a parable. He tells me, with a crooked smile, how the devil tried to steal the Grossmünster bell but was outwitted by the women of Zurich. “You see?” he murmurs. “Hungry men can be tricked, outlasted, turned toward better tasks.” But soon after, his fingers knot in mine, and I know he fears the hunger more than any devil.

And me? Between briefings and the ritual, regulated days—I ache. For sunlit libraries, the uncertain lilt of my students’ questions, the risk of bus tickets bought at random and maps marked with intention and accident. Zurich’s cold clarity can’t quite tame the urge to wander. I miss the old restlessness, the sense of choosing my peril, not wearing someone else’s armour.

Still, at night, the city croons—church bells roaming the darkness, the far-off call of a vagrant tram bell. This place has always been a crossroads; perhaps I am just another legend passing through, marking the marble with the shadow of adventure not yet finished.

And beside me, Tarmo listens for stories he can’t quite name, and in the flicker of firelight or the chill blue of morning, I wonder whether our own myth is one of pursuit or escape, and which version will win.

Sometimes I think I should be embarrassed by how thoroughly I am “owned”—by a man, by a city, by the choreography of threat and longing that follows me through the marble and glass corridors of our exile. There’s irony in it, of course: being someone who corrals danger for a living, and yet finding myself corralled—hedged in by Tarmo’s relentless need, by guards at every threshold, by the impossibility of slipping off for even a solitary hour under the Zurich sky.

I catch myself scoffing, half in jest, at the miracle that I’m not pregnant after the places we’ve claimed: museum stairwells, hidden courtyards, the Astronomical Clock’s shadow, hotel elevators on their slow slide between floors. If there’s a shrine to unapologetic desire in this city, we’re the ones lighting candles at every threshold. And the strangest part is this: the bleak old fears, those nightmares that used to curl up at the end of my bed, have dissipated—not from therapy, not from luck, but from being devoured and remade in the engine of our hunger. Survival, it turns out, can be fervent, messy, and oddly healing. Who knew?

Still, sometimes the joke curdles. Sometimes, marvel edges toward disquiet as I realise how thoroughly Tarmo means to keep me. After one ill-conceived adventure—a single, breathless escape beyond security’s dragnet, just to feel the river air on my skin—he nearly closed the borders of Switzerland for me. Zurich went on lockdown, back-channel calls were made, and every guard’s eyes held a question: how hard is it to cage a bird with an atlas tattooed under her skin?

A part of me yearns for ordinary risk: a day outdoors, the simple adventure of being anonymous and unencumbered. But here, I am marked, claimed, and watched over like a relic too precious for sunlight. I wonder, wryly, if he will ever let me go—or if I’ll ever truly want him to.

Maybe this is love’s truest miracle: that for all the walls we build, desire proves better at breaking them than any army ever could.

That afternoon, Tarmo insists on a walk—a “controlled outing,” as if the city might bend to his will. We end up on the Lindenhof hill, high above the tangle of Bahnhofstrasse, with the Limmat flowing cold and implacable past Roman stones and old guild houses below. Here, Zurich’s roots are visible: Celtic, Roman, Swiss—a city eternal in its layering, each era laid atop the next, none fully letting go.

Tarmo lingers at the railing, the old plain trees leafless against the slate sky, and I sense the tension roiling beneath his collected surface. The guards are near enough to touch; I feel the heat of surveillance rather than sunlight, his world wrapping around me, beautiful and suffocating.

The Lindenhof has its myth, of course. They say that centuries ago, the city’s women, disguised in their husbands’ armour, stood on these very ramparts to fool invaders. In the dim winter light, I picture them: fierce, cunning, refusing to surrender the city or themselves.

I want to tell Tarmo the story, but when I start, he only half-listens, his eyes constantly scanning for risk. “You’d have made a better general than most of those men,” he says, voice tight. “No one would breach your walls.”

The irony twists through me—a city defended by its women, and here I am, yearning to slip these new defences.

“I’m not sure I want to be a fortress forever,” I say quietly. “Sometimes I just want to walk the hill without a shadow at my back.”

He bristles, the lines around his mouth hard. “I keep you close for your own safety. You know what’s out there—what could happen if—”

“If you let go,” I finish for him, angry and aching at once.

Below us, the Limmat glimmers where the sun finds it, cold gold running east. I find myself thinking of the city’s other ghost—the Tatzelwurm, the lake-dwelling dragon said to rise only when the water grows too still. Zurich understands that danger and beauty can never be perfectly separated.

“You can’t lock up the river, Tarmo. It finds its own path,” I say, gaze fixed on the winding water.

He’s silent; myth and reality hang in the air, the story of the armoured women echoing between us. I realise I’ve become my own legend here—a creature both venerated and contained.

His hand finds mine, grip tight enough to bruise. “Someday, maybe—but not yet,” he admits, and I see the storm of love and fear that keeps him from letting go, even as I press, stubborn and alive, against his careful borders.

The city watches, ancient and modern, as our private war wages on: a Viking unwilling to loosen his hold, a scholar remembering that freedom is older—and sometimes braver—than any story about conquest and defence. And above us, the Lindenhof trees keep their secrets, as legends always do.

Author’s Note

For the accidental new readers, if you came here expecting a reliable guidebook to Zurich, well, that was your first mistake. Facts have been liberally seasoned with fiction, legends have been cross-examined until they confessed to things they never did, and I may have taught a few Swiss myths some particularly bad habits. As an Amsterdam native and an anthropologist at heart, I know two things: first, that every city keeps its best stories just out of reach of the tour buses, and second, that the truth is considerably more entertaining when it’s not wearing its Sunday clothes.

Zurich is a city built to be both admired and escaped, often in the same breath. Most of the stories are real, some are decidedly less so, and a few still owe me an explanation. The Lindenhof rampart legends and the Tatzelwurm exist, probably just to prove that truth is stranger than most fiction. The rest came along for the ride because, like most wanderers, my characters (and their author) are rarely content with a single passport or a tidy explanation.

If you notice a narrator who is allergic to melodrama, who laughs as her last defence, or who refuses to take even her own legend at face value—well, blame Amsterdam. Or anthropology. Or the fact that sometimes love and longing are both more dangerous and more absurd than any storybook devil or Swiss dragon.

Thank you for walking these crooked streets with me, for tolerating smuggled wit amid the ghosts and runestones. If you finish this book wanting to climb a hill, question a border, or light a candle to your own unruly heart, then my work here is—as they say in Zurich—more or less accomplished.

May your lifeforce be defiant when banks rise.

I.Ph.